NIGERIAN literature, beginning with pre-independence publications of Amos Tutuola’s The Palmwine Drinkard (1952) and Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart (1958) depict literatures of masculinity. Put differently, the greatness of these novels and others like them, are emphasized in the physical prowess of their protagonists, a virtue attributed to pre-colonial Nigerian societies.

The period in question was a period of the celebration of valour and tenacity. Might was believed to be right and a heroic feat became a communal yard-stick to measure success or otherwise. It is therefore, within this kind of community, for instance, that Achebe’s Okonkwo is created. He is described as a fearless young man of great strength, whose fame is known across the nine villages and beyond as one, whose back has never touched the ground in any wrestling contest. As a result of these qualities, though “still young, he was already one of the greatest men of his time.”

The society had no time to waste with the womenfolk whose significant contributions to communal matters centered around singing and dancing during ceremonies. The women did not fit much into the heroic cadre of the society at that time and, therefore, were not subject of literary imagination or creativity. Indeed, in such a society, being a woman was like being sentenced to a life of insignificance and subsidiary existence. Perhaps, it is for this reason that Okonkwo’s mother hardly exists while his father, Unoka, an efulefu or worthless man who has never cleared even a footpath of his own, receives a mention even if it was a juxtaposition to his son.

Like Achebe, Tutuola’s Drinkard is said to have married the woman whom he rescues from the skull. In line with mythologies, the mythical hero requires a ‘sine qua non’ or what Gerald Moore refers to as “the ever faithful and helpful female companion” (quoted in Little, 1980, p.97). And for this reason, a female is brought in to spice as it were, a masculinist tale.

Wole Soyinka in The Lion and the Jewel very easily makes a caricature of women as foolish in spite of their age. Sadiku is confided in by Baroka and what does she do? She runs to inform her co-wives about the supposed failure of Baroka’s manhood. Eventually, through her own device, hearkens to Baroka’s urge to have the young Sidi in his room and to the eventual doom that befalls the girl’s purity at the hands of the African tortoise himself. Cleverly, Soyinka weaves through the image of the female as probable reason for the destruction of another.

Wole Soyinka in The Lion and the Jewel very easily makes a caricature of women as foolish in spite of their age. Sadiku is confided in by Baroka and what does she do? She runs to inform her co-wives about the supposed failure of Baroka’s manhood. Eventually, through her own device, hearkens to Baroka’s urge to have the young Sidi in his room and to the eventual doom that befalls the girl’s purity at the hands of the African tortoise himself. Cleverly, Soyinka weaves through the image of the female as probable reason for the destruction of another.

The dismal representation of women in early Nigerian literature is not unconnected with the patriarchal nature of traditional societies, in addition to the colonially inspired value judgment of the time. Women in most traditional societies were hardly visible, they were restricted to domestic chores and subsistence farming while the struggle for independence spearheaded by men, focused attention on the colonial model of civilization. Western education became the yardstick for measuring civilization and schools then were dominated by men.

Consequently, early writers were more concerned about the dilemma of the man rather than the misery of those women stuck in the woods, wading through the mud of life unnoticed. For these reasons, women were referred to in abstract terms as ‘mother earth’ ‘river goddesses’ etc or as mistresses to kings or as adornment in palaces as is common in Hausa literature of northern Nigeria.

However, independence came with a new vision and wider vistas of life. In Achebe’s post-independence novels like No longer at Ease or T. M Aluko’s Chief the Honourable Minister for example, we see women equally engaged with the men in the pursuit of western education but rather than study to become doctors, Clara and Gloria both study nursing. These writers equip the female with just enough education to enable them play the roles of girlfriends or good-time girls which sadly, becomes their ultimate destination. While for wife, Alade Moses for instance, will have the less attractive and unsophisticated Bose who is ready to remain at home bearing children in quick succession, giving him more reasons to continue with his philandering outside.

Such stereotyped representations of the female were in fashion in most post-independence Nigerian novels. This period also introduced into the Nigerian literary world the image of the female as a ‘free’ woman. This new image of the woman is different from the girlfriend or good-time girl image in that, this kind of woman has a dogged mind of her own albeit, not so developed through formal training as it is more from adaptations in the fast growing cities of the time. Cyprian Ekwensi’s People of the City readily comes to mind here.

The character, Beatrice, wants to fulfill her desires and enjoy her life to its full by choosing her men from the lot at any given time. Though bonded by native-law to Grunnings, the European engineer, Beatrice is attracted to the world of glamour and seduction. Here, Ekwensi adds a new dimension to the image of the female who is bonded in marriage and yet chooses to play the man’s game by moon-lighting outside. In yet another of his works, in fact, his most popular novel, Ekwensi presents, sometimes with graphic details, the further degeneration of the female as she plays her role as a courtesan or prostitute.

The courtesan or prostitute again differ from the ‘free’ woman in the sense that whereas, the ‘free’ woman can be kept and provided for by a man to whom she owes her loyalty, the courtesan or prostitute prefers her ‘liberty’ or ‘freedom’ to glide as it were, from one man to another who is ready to pay her fee. Jagua Nana in the novel of same title and Madame Obbo in I.N.C Aniebo’s The Journey Within, both exemplify this representation of the female.

Giving close look at these representations of the female in Nigerian literature, it becomes evident that stereotyping of these nature were carried out primarily by male writers who formed the early teachers of literature. As mentors, therefore, they fostered a lot of influence and indoctrination was easy for the up-coming generation. Although women played significant roles in history and culture, the male writers of Achebe’s era conveniently ignored them. It was not until Nigerian women themselves woke up to their inner cries by beginning to write the woman’s own travails from the point of view of women did we start to have proper representation of females in our literature.

In the novels of Flora Nwapa, Nigeria’s first published female novelist, and the plays of Zulu Sofola, we see women as backbones of families by actively engaging in commerce and agriculture. More often than not, women are the stabilizing force in men’s life, a fact that only began to rear up its head when women began to tell their own stories.

The travails of Efuru and Idu, both heroines of novels of same title and Adah in Buchi Emechata’s Second-Class Citizen clearly represent women as more enduring in the face of difficulties, more resourceful in the home front and finance management and better composed in distress situations. Adah for example becomes a predator at the hands of Francis and his family members because of her resourcefulness and Efuru’s husband, Adizua, squanders her money on his concubines. The realistic representation by these female writers may not be far from the belief that most women tend to be autobiographical in their approach to handling issues affecting other women while the male writers often adopt surrealistic approach in their handling of issues affecting women.

The travails of Efuru and Idu, both heroines of novels of same title and Adah in Buchi Emechata’s Second-Class Citizen clearly represent women as more enduring in the face of difficulties, more resourceful in the home front and finance management and better composed in distress situations. Adah for example becomes a predator at the hands of Francis and his family members because of her resourcefulness and Efuru’s husband, Adizua, squanders her money on his concubines. The realistic representation by these female writers may not be far from the belief that most women tend to be autobiographical in their approach to handling issues affecting other women while the male writers often adopt surrealistic approach in their handling of issues affecting women.

Furthermore, the Nigerian civil war of 1966-1970 also brought with it a wave of awareness to women and their representation in Nigerian literature took a new turn. Nwapa’s Women at War for example, catalogues the events of the war from the point of view of women. She presents women as the unsung heroes of the war. If men fought militarized battles with canons and guns, women similarly fought against the forces of air-raids, hunger and diseases in addition to physical and moral rape. Henceforth, women’s roles could no longer be over looked and they realized their own abilities and contributions to their societies.

This new dimension given to the role of women in Nigerian literature gave second generation Nigerian writers a better view of women. Coupled with the Marxist, Leninist and feminist tendencies of the time, Nigerian writers of the late 1970s and 1980s were more plausible in their representation of women. Indeed, writers such as Femi Osofisan would go all the way back into history to recreate the dynamism and resourcefulness of women like Moremi to which the playwright refers to as a discovery of a sweet-thing, hence the title, Morountodun.

Moremi, a woman of “tremendous courage” (pp35-36), stakes her life to bring peace to her people because “our men tremble by their household shrines, their prayers stuck in their teeth. Our warriors are beginning to babble like Obatala’s misfits… your priests are again going to pieces in helpless rage, their vaunted charms, now impotent like Osanyin left in the rain” (p 37). Finally, to convince her husband, Oronmiyon, of the urgent need for something to be done she says, “when muscles slacken suddenly in the midst of dispute, they say it is time to use other tactics. I Must Go” (p 38). Such literary depiction of the courage of the female especially, by the male writers, was non-existent amongst first generation writers.

Similarly Fred Agbeyegbe in the play The King Must Dance Naked, demystifies the kingship institution where only men must rule by tactically making a woman king. Also, in Bode Sowande’s Farewell to Babylon the Marxian revolution that seeks to bring change in the society is masterminded by women. In fact, a woman plays the role of a commander in the struggle.

Among their counterparts from the northern states of the country, women were also positively represented during this period. In the Hausa novels of Abubakar Imam, Magana Jari Ce for instance, the story of Queen Amina of Zaria is retold with a flavour that gladdens the heart just as other women are seen as agents of social change, political control, moral guides and communal counsellors. Also, Aliyu Nasidi’s poetry of colonial struggle in northern Nigeria glorifies the strength or powers of women as farmers of ‘wild’ chiefs and other cadres of traditional leadership.

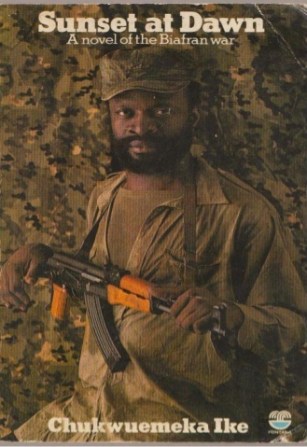

Also, Zainab Alkali’s The Descendants (2005) is worth a mention. In this work, Seytu is portrayed as rising from a very humble background to become a medical doctor. One of the closest to this kind of elevation of the female has been in Chukwuemeka Ike’s Sunset at Dawn, where a female is presented as a radiographer. Consequent upon these writings by men and also due to the fact that more women began in earnest, to write about their unending problems, their awakening have spurred the conscience of the male writers to represent the female gender in a more realistic manner.

Also, Zainab Alkali’s The Descendants (2005) is worth a mention. In this work, Seytu is portrayed as rising from a very humble background to become a medical doctor. One of the closest to this kind of elevation of the female has been in Chukwuemeka Ike’s Sunset at Dawn, where a female is presented as a radiographer. Consequent upon these writings by men and also due to the fact that more women began in earnest, to write about their unending problems, their awakening have spurred the conscience of the male writers to represent the female gender in a more realistic manner.

Finally, as women and men with sympathetic feelings to the woman’s cause continue to recreate the image of women as they see them, our national literature will eventually wear its proper garment and stand out to compete for instance, with Francophone literature especially, the works of Sembene Ousmane who is able to strike a balance between his male and female characters. It is sad to point out here, that two of Africa’s best read authors, indeed, Nigeria ‘s very own Achebe and Soyinka have failed in their works to create an outstanding female character in the semblance of Osofisan’s recreation of Moremi. A character who is rounded enough as to exhibit leadership qualities or one that can emancipate herself and others like her from oppressive circumstances within their works.

To conclude, it is pertinent to commend efforts made by second generation and contemporary writers for the positive shift in women’s roles in our literatures from the traditional portrayal of the status of women as persons relating always to others and depending on others especially the men, for every decision, to the ‘new woman’ image who possesses a well-controlled determination to get what she wants through her own articulations.

It is heart-warming therefore, that this generation of writers have seen the significant contribution of women to society as to want to break historical, cultural and mythical barriers as to represent them in their proper perspectives. Women are no longer accepting representations in our literature as mere biological species but as a social class to be reckoned with.

———————–

Dr. Muhammed, a lecturer at the University of Maidguru, presented this paper at ANA Lagos and WRITA Lagos special Lovers’ Day reading.

good work keep it up

brief and inspiring

the women also ve a saying towards the development of the country

Not surprising, write more.

It is true that even canonised pieces in Nigerian literature have failed to give women a fair hearing. One tends to wonder whether this stems from inherited fear of pushing against the tides of established culture, not receiving favourable appreciation by the vastly masculinist home audience, or simply a fear of acknowledging the noble and startlingly diverse capabilities of women beyond beauty, adornment or the sadly celebrated fickleness of the sex. It’s heart-warming to see all that changing & to be part of the begining of a recognition of women who, together with charm & beauty, also have intellectual competence, courage & ability to spear head change. Thanks for the article, ma!

It’s so sad that even our so called educated writers still portray women as if they don’t exist. Great Article ma. Expecting more of it.

Very good read…kept me glued.